Some questions:

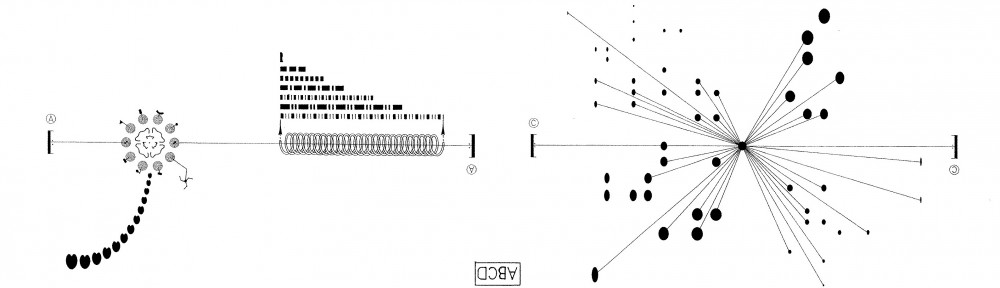

• We saw some of what can be gained from studying the material forms of the books that contain music, as well as from studying the notation itself; how different is this with graphic scores?

• how does knowledge of other media and cultural context affect our understanding of the notation of the 1960s?

• can music of this period be understood just from recordings or live performance?

• should we assume that the purpose(s) of notation is always the same? What factors might alter the purpose of a score?

Last week, our discussion revolved around one of the central questions of our course: what is notation? However, the readings provoked me towards ruminating on another question. Namely, what is music? I wish that we could gather composers engaged in crafting graphic scores and pose them this question in a single room, because I think that their definition of music would be influenced by the manner in which they notate it.

In his article, “Sound, Code, and Image,” Walters offers several tantalizing quotes from various composers who have participated in graphic score notation. Howard Skempton believes that graphic scores say much more about how music works than do scores written by Beethoven, for example (30). Indeed, Skempton argues that “a score has a life of its own” (30). What can we say about Skempton’s understanding of music from these words? Composer John Woolrich also offers an interesting statement: “Notation is to do with hints rather than absolute instruction. You are trying to convey the big image” (28). What exactly is “the big image”? And is it significant that he chooses the word “image” rather than “sound”?

One of the graces of graphic scores is that they allow for the interpretation and production of the piece they represent to be dependent on the individual making the music. The meaning of music becomes flexible because it depends on how it is created and by whom. As Walters writes, “the visual aesthetic of this work evokes an imagined music in the observer’s mind, an invisible music more ascetic, beautiful, and formally Modern than any earthly ensemble could produce with real instruments” (26-7). In this portrayal of music, music does not have to be something which is physically sounded, but rather felt internally. It can enter the human body through the eyes rather than the ears.

If only because it is interesting to ponder about, I am struggling to give a definition to music when it can be “invisible” and soundless, and wonder if anyone else has thoughts about the definition of music to graphic score composers/notators/readers.

My current research explores the nature of sound, personal experience and musical notation in association with the intentions of the composer. What i feel may be relevant to the question is that the nature of sound is that it is disruptive, no one performance can ever be the same as it will always be embellished with the time and space into which it is being experienced.

John Cage redefined music as the “organisation of sound” interrelating the concept of vision and hearing, space and time.

Notation can be seen to represent the activity of sound, a preservation or memory of sonorous occurrences. Musical notation is the visualization of sound, an expression from the composer. A form of communication to the musician, the same way, in which we use words to represent speech, and speech to articulate thought. Language has found a visual form through writing, sound and music has found a visual form through scores. Each viewer experiences music and sound differently to how their neighbour experiences it. The movement of the person in front at a concert will alter your experience of that sound. If sound is a vibration and someone disrupts that vibration then they have disrupted and therefore altered that sound so it becomes a new composition in itself. A chance composition created as a result of what was unintended by the composer.

To define music one must consider its association with sound, and sound can never reflect anything other than what it is. As a sonorous experience without any visual sound becomes it’s own entity. John Cage described music as someone talking, whereas sound is just sound, it’s not trying to say anything.

So if music is someone talking that’s saying music is a form of communication.

What i find interesting within graphic notation is where the piece lies, posing the question of authorship. If the work is the score as a visual piece itself, then the composer is the author, however once the piece is performed and the musician interprets the score than the piece may fall within the realm of collaboration so it becomes a shared authorship?