The English composer Cornelius Cardew (1936-81) was among the most adventurous, controversial and innovative musicians of his generation. After a brief affiliation with Stockhausen and the European avant-garde, he became engaged with the aesthetic ideas of John Cage and the New York school. A leading figure in the experimental music of the 1960s and ’70s, Cardew is widely acknowledged as a pioneer of graphic notation, free improvisation, and performer involvement. As well as extending the boundaries of music in unprecedented directions, he inquired deeply into its social relevance and meaning, which led him to become a political activist.

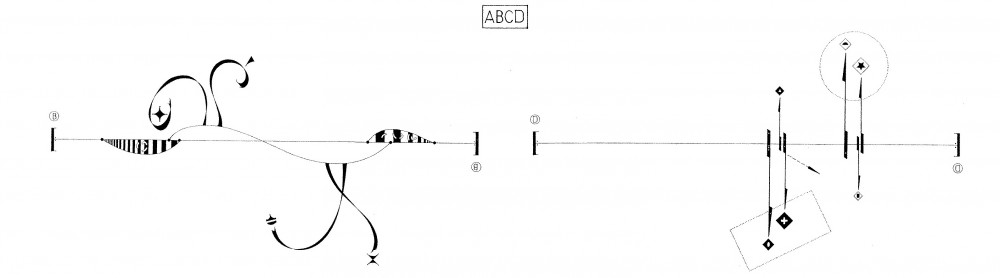

Treatise contains no specific musical instructions; rather, it comprises shapes, numbers, symbols, and some standard notation devices subject to various degrees of distortion. Cardew does not provide a key to deciphering the pages, necessitating that musicians realize the work according to their own rules. Despite its historical significance and musical potential, Treatise is rarely performed. There are recordings by pianist John Tilbury (who worked closely with Cardew) and AMM percussionist Eddie Prevost (on Cornelius Cardew Piano Music 1959-70, for the Matchless label), but only one performance of the entire work, the live recording of the QUaX Ensemble, from 1967.

The Vocal Constructivists made a commitment to performing the work in its entirety. Calculating roughly 20 seconds per page, this yielded performances of just over an hour.

Cardew’s Treatise Handbook (1971) suggests the following merits.

Virtues that a musician can develop:

- Simplicity. Where everything becomes simple is the most desirable place to be. But … the simplicity must contain the memory of how hard it was to achieve.

- Integrity. What we do in the event is important – not only what we have in mind. The difference between making the sound and being the sound.

- Selflessness. To do something constructive you have to look beyond yourself. The entire world is your sphere if your vision can encompass it … You should not be concerned with yourself beyond arranging a mode of life that makes it possible to remain on the line, balanced. Then you can work, look out beyond yourself.

- Forbearance. Improvising in a group you have to accept not only the frailties of your fellow musicians, but also your own. Overcoming your instinctive revulsion against whatever is out of tune (in the broadest sense).

- Preparedness … for no matter what eventuality … or simply Awakeness … A great intensity in your anticipation of this or that outcome.

- Identification with nature. The best is to lead your life, and the same applies in improvising: like a yachtsman to utilise the interplay of natural forces and currents to steer a course. My attitude is that the musical and real worlds are one. Musicality is dimension of perfectly ordinary reality. The musician’s pursuit is to recognize the musical composition of the world.

- Acceptance of death. From a certain point of view improvisation is the highest mode of musical activity, for it is based on the acceptance of music’s fatal weakness and essential and most beautiful characteristic – its transience … The performance of any vital action brings us closer to death; if it didn’t it would lack vitality. Life is a force to be used and if necessary used up.

Materials on Cornelius Cardew:

CORNELIUS CARDEW WORKS BY GENRE

http://www.users.waitrose.com/~chobbs/tilburycardew.html